Gulfport, Mississippi

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

Gulfport, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

Downtown Gulfport | |

| Motto: Anchored in Excellence[1] | |

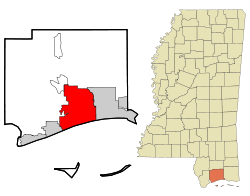

Location within Harrison County | |

| Coordinates: 30°24′6″N 89°4′34″W / 30.40167°N 89.07611°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Harrison |

| Incorporated | July 28, 1898 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong mayor–council |

| • Body | Gulfport City Council |

| • Mayor | Billy Hewes (R) |

| Area | |

• City | 64.01 sq mi (165.79 km2) |

| • Land | 55.62 sq mi (144.06 km2) |

| • Water | 8.39 sq mi (21.73 km2) |

| Elevation | 20 ft (6 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 72,926 |

| • Density | 1,311.08/sq mi (506.21/km2) |

| • Urban | 236,344 (US: 169th)[4] |

| • Urban density | 1,401.5/sq mi (541.1/km2) |

| • Metro | 416,259 (US: 133rd)[3] |

| Demonym | Gulfporter |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 39501-39503, 39505-39507 |

| Area code | 228 |

| FIPS code | 28-29700 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0670771 |

| Website | www |

Gulfport (/ˈɡʌlfˌpɔːrt/ GUHLF-port) is a city in and a co-county seat of Harrison County, Mississippi, United States. It is the second-most populous city in Mississippi, after Jackson, and part of the Gulfport–Biloxi metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, Gulfport has a population of 72,926; the metro area has a population of 416,259. Gulfport lies along the gulf coast of the United States in southern Mississippi, taking its name from its port on the Gulf Coast on the Mississippi Sound.

Gulfport emerged from two earlier settlements, Mississippi City and Handsboro. Founded in 1887 by William H. Hardy as a terminus for the Gulf and Ship Island Railroad, the city was further developed by Philadelphia oil tycoon Joseph T. Jones, who funded the railroad, harbor, and channel dredging. The city was officially incorporated in 1898. By the early 20th century, Gulfport had become the largest lumber export city in the United States, though this faded with the depletion of Mississippi's Piney Woods. The city transitioned into tourism through its white beaches, grand hotels, and significant casino gaming operations.

The largest sectors of Gulfport's economy include military operations, tourism, healthcare, and maritime commerce. The city is home to the Naval Construction Battalion Center, Gulfport Combat Readiness Training Center, and Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College. The Port of Gulfport serves as one of the busiest ports in the Gulf of Mexico, while Gulfport-Biloxi International Airport provides commercial air service to the region. Despite significant impacts from Hurricane Camille in 1969 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the city has consistently rebuilt and expanded its infrastructure and facilities.

History

[edit]Two villages predated the founding of Gulfport: Mississippi City, located along the gulf, and Handsboro, founded in the 1800s along the northern bayous.[5][6] Mississippi City was born out of the Mississippi City Company that was formed in 1837 to build a town to serve as the terminus for the Gulf and Ship Island Railroad.[7][8] The purpose of the railroad was to transfer yellow pine for ship-based trade.[9] While a depression led to the abandonment of the railroad, the town was nevertheless built and later made the county seat upon the creation of Harrison County in 1841.[5][10]

The Gulf and Ship Island Railroad company was later reorganized and selected William H. Hardy as its president. Desiring to connect the railroad from the town of Hattiesburg, which he founded, to the coast, he steered away from Mississippi City because of its lack of proximity to deep water.[10] He selected the site of Gulfport in 1887, and the town was founded that year.[11] Because of the cost of the project, Hardy went bankrupt in 1893, and the town became a ghost town.[10] However, Philadelphia oil tycoon Joseph T. Jones purchased the company.[10][11] Jones funded not only the railroad, but much of the city, the harbor, and the dredging of the channel.[11] In 1888, the city was given its name from the Jackson Clarion-Ledger editor, R. H. Henry after a conversation between him and Hardy.[11] On July 28, 1898, the city was incorporated.[5] In 1902, Harrison County voted to move the county seat to Gulfport.[5]

In 1900, the railroad was completed, and in 1902 the Port of Gulfport was completed.[10] On April 28, 1904, the Treasury Department changed the port of entry for the district of the Pearl River from Shieldsboro to Gulfport.[12] At the time, the Gulfport port had greater ease of access than comparable ports like Mobile or New Orleans.[10] The port soon made Gulfport the largest lumber export city in the United States, shipping over 293 million feet of lumber in 1906; however, the depletion of the yellow pine ended this status in the early 20th century.[10]

At the turn of the century, Gulfport began to experience notable growth: by 1900, the population hit 1,000, and by 1910, over 6,000.[10] As a result, the fire department and sanitation services were established, and by 1903, the county courthouse was built.[9][10] The Louisville and Nashville railroad line also began serving the city around this time at Gulfport Station (then the Union Depot).[10] In 1910, the U.S. Post Office and Customhouse was built,[13] and in March 1916, the construction of a Carnegie Library was announced by the mayor.[14] Other impressive developments include the building of the Great Southern Hotel, the construction of an electric plant (later managed by Mississippi Power), and a streetcar line.[10]

In 1917, the city was set to hold the Mississippi Centennial Exposition, but upon the U.S. entering World War I, the plans were abandoned. The building complex created for the exposition was transferred to the U.S. Navy as a training center. The lands were eventually transitioned into a Veterans Administration Hospital, which operated until 2005.[10][15] The 1920s saw a construction boom with buildings like the Hotel Markham and the Bank of Gulfport being completed.[10] By the 1930s, the population had increased to over 12,000, with growth continuing into the 1940s.[10]

During World War II, two military bases were built in Gulfport. Camp Hollyday, established in 1942, would later become the home base for the Naval Construction Battalion Center.[10] Also in 1942, the U.S. Army Air Corps constructed a training base for heavy bomber crews known as Gulfport Army Airfield.[16] After the war, the base was declared excess, and the city purchased most of the facilities for a new Gulfport Municipal Airport (the first airport was dedicated in 1930).[16][17] In 1954, the U.S. Air Force resumed use of the facilities they still owned as Gulfport Air Force Base to train Air National Guard units.[17] This lasted until 1958,[18] when the facilities were transferred to the Mississippi Air National Guard as the Gulfport Combat Readiness Training Center.[16]

By 1950, the population had grown to around 22,000 and by 1960, 30,000.[10] Around the time of the Biloxi wade-ins, Gulfport had its own protest wade-in in 1960.[19] In 1965, the city annexed the original Mississippi City and Handsboro area.[9] On August 17, 1969, Gulfport and the Mississippi Gulf Coast were hit by Hurricane Camille, the second-strongest hurricane to make landfall in the U.S. in recorded history.[20] The most heavily damaged part of Gulfport was the waterfront areas: storm waters in Gulfport reached 21 feet, and the port of Gulfport was nearly completely destroyed. Otherwise, the downtown and inland areas received small amounts of structural damage.[21]

In 1976, the Armed Forces Retirement Home relocated from Philadelphia to Gulfport on the land of the former Gulf Coast Military Academy. The facility was destroyed in 2005 by Hurricane Katrina but rebuilt as a much larger facility in 2010.[22] A new county courthouse was built in 1977. In 1993, the city opened its first two casinos, and later that year in December, the city annexed 33 square miles (85 km2) north of Gulfport. This annexed land included Turkey Creek, a historic community founded by emancipated slaves before the founding of Gulfport.[23] In 2003, the Dan M. Russell Jr. United States Courthouse was completed.[9]

On August 29, 2005, Gulfport was hit by the strong eastern side of Hurricane Katrina with wind speeds of at least 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) and storm surge of at least 19 feet (5.8 m).[24][25] 9,571 houses were damaged or destroyed, and the town was left with a $3 million deficit. The city received over $300 million in federal aid which it used to repair infrastructure and facilities for essential services.[26] In 2020, on the 15th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, the Mississippi Aquarium opened, replacing a dolphin-oriented facility destroyed by the hurricane.[27][28]

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 64.2 sq mi (166.4 km2), of which 56.9 sq mi (147.4 km2) is land and 7.3 sq mi (19.0 km2) (11.40%) is water.

The Gulfport Formation in Harrison County is described as barrier ridge composed of white, medium- to fine-grained sand, yellow-orange near surface. Thickness ranges from 5.0 to 9.5 m. It overlies Biloxi Formation. Age is late Pleistocene.[29]

Gulfport Formation is limited to a 1- to 3-km-wide discontinuous barrier ridge belt that borders the Gulf mainland shore. It commonly overlies Prairie Formation (alluvium) landward and Biloxi Formation (shelf deposits) near shore. The formation grades upward from poorly to moderately sorted shoreface sands to foreshore sand and dunes. The unit extends from Gulfport, MS, eastward to the mouth of the Ochlockonee River, Franklin County, Florida and was deposited during the Sangamonian.[29]

Neighborhoods

[edit]The city listed 39 official neighborhoods in 2000. These neighborhoods are sometimes subdivisions or accumulations of gradual home development.[30] These include:

- Lyman

- Orange Grove

- Biloxi River

- Lorraine

- The Reserve

- Pine Hills

- Bayou Bernard Industrial District

- Bayou View North

- The Island

- Fernwood

- Handsboro

- College Park

- Silver Ridge

- Great Southern

- Mississippi City

- Gooden

- East Park

- Bayou View South

- Magnolia Grove

- East Beach

- Broadmoor

- Soria City

- CBD

- State Port & Jones Park

- West Beach

- Gaston Point

- Fairgrounds

- Central Gulfport

- 25th Avenue Commercial

- Original Gulfport

- Mid-City

- Brickyard Bayou

- North Gulfport Industrial Center

- Turkey Creek

- North Gulfport

- CB Base

- Gulfport Heights

- Forest Heights

- Sports Super Complex

Climate

[edit]Gulfport has a humid subtropical climate, which is strongly moderated by the Gulf of Mexico. Winters are short and generally mild; cold spells do occur, but seldom last long. Snow flurries are rare in the city, with no notable accumulation occurring most years. Summers are generally long, hot and humid, though the city's proximity to the Gulf prevents extreme summer highs, as seen farther inland. Gulfport is subject to extreme weather, most notably tropical storm activity through the Gulf of Mexico. The all-time record high for the city is 107 °F (41.7 °C), set on August 26, 2023, and the record coldest is 1 °F (−17.2 °C) on February 12, 1899. Climate records for the city date back to 1893; however, until 1998 records were stitched with neighboring Biloxi.

| Climate data for Gulfport, Mississippi (Gulfport-Biloxi Int'l) 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 82 (28) |

87 (31) |

89 (32) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

103 (39) |

103 (39) |

107 (42) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

88 (31) |

83 (28) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 73.8 (23.2) |

75.5 (24.2) |

81.4 (27.4) |

84.5 (29.2) |

90.5 (32.5) |

94.6 (34.8) |

96.9 (36.1) |

96.2 (35.7) |

93.8 (34.3) |

88.6 (31.4) |

81.2 (27.3) |

75.9 (24.4) |

98.2 (36.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 61.3 (16.3) |

64.8 (18.2) |

70.4 (21.3) |

76.5 (24.7) |

83.6 (28.7) |

88.7 (31.5) |

90.4 (32.4) |

90.7 (32.6) |

87.8 (31.0) |

79.9 (26.6) |

70.0 (21.1) |

63.5 (17.5) |

77.3 (25.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 51.8 (11.0) |

55.5 (13.1) |

61.1 (16.2) |

67.5 (19.7) |

75.0 (23.9) |

80.9 (27.2) |

82.7 (28.2) |

82.6 (28.1) |

79.2 (26.2) |

70.0 (21.1) |

59.6 (15.3) |

54.0 (12.2) |

68.3 (20.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 42.4 (5.8) |

46.2 (7.9) |

51.8 (11.0) |

58.4 (14.7) |

66.4 (19.1) |

73.2 (22.9) |

74.9 (23.8) |

74.6 (23.7) |

70.6 (21.4) |

60.1 (15.6) |

49.2 (9.6) |

44.6 (7.0) |

59.4 (15.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 24.6 (−4.1) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

33.1 (0.6) |

41.3 (5.2) |

52.2 (11.2) |

64.8 (18.2) |

69.8 (21.0) |

68.7 (20.4) |

58.6 (14.8) |

43.1 (6.2) |

32.3 (0.2) |

29.1 (−1.6) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 4 (−16) |

1 (−17) |

22 (−6) |

34 (1) |

43 (6) |

52 (11) |

58 (14) |

59 (15) |

42 (6) |

33 (1) |

24 (−4) |

9 (−13) |

1 (−17) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.87 (124) |

4.44 (113) |

5.22 (133) |

5.51 (140) |

4.74 (120) |

6.89 (175) |

7.21 (183) |

6.53 (166) |

5.18 (132) |

3.71 (94) |

4.03 (102) |

4.49 (114) |

62.82 (1,596) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 In) | 8.9 | 9.3 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 12.0 | 12.8 | 13.9 | 9.2 | 7.9 | 8.3 | 10.5 | 116.5 |

| Source: NOAA[31][32] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]2020 census

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 1,060 | — | |

| 1910 | 6,386 | 502.5% | |

| 1920 | 8,157 | 27.7% | |

| 1930 | 12,547 | 53.8% | |

| 1940 | 15,105 | 20.4% | |

| 1950 | 22,659 | 50.0% | |

| 1960 | 30,204 | 33.3% | |

| 1970 | 40,791 | 35.1% | |

| 1980 | 39,676 | −2.7% | |

| 1990 | 40,775 | 2.8% | |

| 2000 | 71,127 | 74.4% | |

| 2010 | 67,793 | −4.7% | |

| 2020 | 72,926 | 7.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[33] 2018 Estimate[34] 2020 census[35] | |||

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[36] | Pop 2010[37] | Pop 2020[38] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 43,337 | 37,038 | 34,382 | 60.93% | 54.63% | 47.15% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 23,692 | 24,266 | 28,287 | 33.31% | 35.92% | 38.79% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 284 | 223 | 293 | 0.25% | 0.24% | 0.4% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 872 | 1,134 | 1,147 | 1.53% | 1.95% | 1.57% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 62 | 87 | 114 | 0.05% | 0.05% | 0.16% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 72 | 69 | 239 | 0.12% | 0.13% | 0.20% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 994 | 1,457 | 3,449 | 1.14% | 1.50% | 4.86% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,814 | 3,519 | 5,015 | 2.11% | 5.50% | 6.88% |

| Total | 71,127 | 67,793 | 72,926 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 72,926 people,[35] 25,559 households, and 15,584 families residing in the city.

Gulfport is part of the Gulfport–Biloxi metropolitan area, which has a population of 416,259.[3][35]

Economy

[edit]According to Gulfport's 2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[39] the top employers in the city were:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Memorial Hospital | 4,953 |

| 2 | Naval Construction Battalion Center | 4,876 |

| 3 | Gulfport School District | 2,724 |

| 4 | Harrison County School District | 2,086 |

| 5 | Island View Casino | 1,976 |

| 6 | Hancock Bank | 864 |

| 7 | Mississippi Power | 728 |

| 8 | Trent Lott Training | 636 |

| 9 | Wal-Mart | 585 |

| 10 | City of Gulfport | 564 |

Tourism

[edit]From its beginnings as a lumber port, Gulfport evolved into a diversified city. With about 6.7 miles (10.8 kilometres) of white sand beaches along the Gulf of Mexico, Gulfport has become a tourism destination, due in large part to Mississippi's coast casinos. Gulfport has served as host to popular cultural events such as the "World's Largest Fishing Rodeo," "Cruisin' the Coast" (a week of classic cars), "Black Spring Break" and "Smokin' the Sound" (speedboat races). Gulfport is a thriving residential community with a strong mercantile center. There are historic neighborhoods and home sites, as well as diverse shopping opportunities and several motels scattered throughout to accommodate golfing, gambling, and water-sport tourism. Gulfport is also home to the Island View Casino, one of twelve casinos on the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

Arts and culture

[edit]

Mississippi Aquarium opened August 29, 2020.[40] The 5.8-acre (2.3 ha) complex incorporates both indoor and outdoor habitats with more than 200 species of animals and 50 species of native plants.[41]

Fort Massachusetts is a fort on West Ship Island along the coast. It was built following the War of 1812 and remained in use until 1903. Currently, it is a historical tourist attraction within the Gulf Islands National Seashore.

Turkey Creek Community Historic District is a settlement established by emancipated African Americans during the Reconstruction Era after the American Civil War.[42]

Government

[edit]Gulfport uses a strong mayor-council form of government.[43] The city is subdivided into seven wards, where members are elected as part of the Gulfport City Council.[44] The current mayor is Billy Hewes who is serving his third term in office.[45]

The Gulfport Police Department has 160 sworn personnel and 80 civilian staff. It is assisted by the U.S. Coast Guard, which operates 9 boats out of the port of Gulfport, 4 of which are Patrol Boats. The Gulfport station has 110 members which include Active, Reserve and Coast Guard Auxiliary who respond to an average of 300 search and rescue cases annually.

The Gulfport Fire Department was founded in 1908 and currently provides fire suppression, HAZMAT response, and technical rescue services within the city limits of Gulfport, Mississippi . The GFD operates out of 11 active stations and is staffed by professional firefighters.[46] The GFD works in conjunction with American Medical Response for EMS related emergencies.

Education

[edit]

The City of Gulfport is served by the Gulfport School District and the Harrison County School District. The Harrison County Campus of Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College is also located in Gulfport.[47]

Before Hurricane Katrina, William Carey University had a satellite campus in Gulfport. In 2009, the university moved to its new Tradition Campus, constructed off Mississippi Highway 67 in north Harrison County.[48]

The Gulf Park Campus of the University of Southern Mississippi is located in Long Beach, just west of Gulfport. In 2012, repairs and renovations to campus buildings were still in progress following extensive damage in 2005 by Hurricane Katrina.[49]

Media

[edit]Headquartered in Gulfport,[50] The Sun Herald is the local newspaper for Gulfport, Biloxi, and other Gulf Coast cities.[51] The paper won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize in journalism for its Katrina coverage.[52]

There are six FM radio stations licensed in Gulfport: W209CF 89.7, WA0Y 91.7 (American Family Radio), WGBL 96.7, WGCM-FM 102.3, WAIP-LP 103.9, and WLGF 107.1 (K-Love).[53] There are also three AM radio stations licensed in Gulfport, all with FM translators: WQFX 1130 (W254DJ 98.7), WGCM 1240 (W265DH 100.9), and WROA 1390 (W261CU 100.1).[54]

It is also served by two television stations, the ABC affiliate WLOX and CBS affiliate WLOX-DT2,[55] as well as the Fox affiliate WXXV on 25.1, NBC affiliate on 25.2, CW+ affiliate on 25.3, and Defy TV affiliate on 25.4.[56] WLOX won the Peabody Award for its Hurricane Katrina coverage.[57]

Movies and TV series filmed in Gulfport include the 2016 film Precious Cargo,[58] the 2017 TV movie Christmas in Mississippi,[59] the 2015 TV series The Astronaut Wives Club,[60] and other productions.

Transportation

[edit]

Gulfport/Biloxi and the Gulf Coast area is served by the Gulfport–Biloxi International Airport.

The Coast Transit Authority provides bus service to the region with fixed-route and paratransit services.

Major roads and highways serve Gulfport. Interstate 10 runs east–west through the middle section of Gulfport. U.S. 90, following the coast in this region, runs east–west through the downtown area. U.S. 49 from the north terminates in Gulfport.

Until Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Amtrak's Sunset Limited from Los Angeles to Orlando made stops in Gulfport station.[61][62] Well into the 1960s, the Louisville and Nashville ran several trains daily, making stops in Gulfport--Crescent, Gulf Wind, Humming Bird, Pan-American and Piedmont Limited—varied destinations including New Orleans, Cincinnati, Atlanta, New York City and Jacksonville.[63] Amtrak service is expected to return in 2025 with the Gulf Coast Limited (new name has yet to be determined) and will connect Gulfport to cities along the Gulf Coast through Gulfport Station.[64]

Notable people

[edit]- Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, former NBA point guard for the Denver Nuggets, Sacramento Kings and Vancouver Grizzlies[65]

- Stacey Abrams, American politician, lawyer, and author[66]

- Thomas H. Anderson, Jr., Ambassador of the United States to Barbados, Dominica, St. Lucia, Antigua, St. Vincent, and St. Christopher-Nevis-Anguilla from 1984 to 1986, was born in Gulfport[67]

- Tommy Armstrong, Jr., quarterback for the Nebraska Cornhuskers[68]

- Jerome Barkum, former wide receiver and tight end for the New York Jets from 1972 to 1983 in the National Football League[69]

- Milton Barney, 1990 AFL Ironman of the Year

- William Joel Blass, attorney and educator[70]

- Katie Booth (scientist), biomedical chemist and civil rights activist

- Timmy Bowers, professional basketball player[71]

- Rod Davis, professional football player, played for the Minnesota Vikings[72]

- Brett Favre, quarterback in the National Football League for the Green Bay Packers, New York Jets and Minnesota Vikings, born in Gulfport[73]

- William H. Hardy, co-founder of the city of Gulfport[74]

- Josh Hayes, professional motorcycle roadracer, AMA Superbike Championship title winner[75]

- William Gardner Hewes, politician and Mayor of Gulfport[76]

- Jonathan Holder, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Boyce Holleman, attorney, politician and actor[77]

- Jaimoe, original member and drummer of the Allman Brothers Band, grew up in Gulfport

- Joseph T. Jones, co-founder of the city of Gulfport[78]

- Matt Lawton, former Major League Baseball player best known for his stint with the Minnesota Twins[79]

- Matt Luke, former head coach of the Ole Miss Rebels football team of the University of Mississippi.

- Stanford Morse (1926-2002), member of the Mississippi State Senate, 1956–1964; Republican candidate for lieutenant governor in 1963.[80]

- Brittney Reese, long jumper, Olympic gold medalist[81]

- John C. Robinson (1903-1954), "The Brown Condor", aviator and civil rights activist

- Stuart Roosa, Colonel, US Air Force, Apollo 14 astronaut, Command Module Pilot. Brought seeds to moon that germinated in space[82]

- Tiffany Travis, former WNBA Basketball player, played for Charlotte Sting[83]

- Natasha Trethewey, Pulitzer Prize winning poet, former Poet Laureate of the United States, and Professor at Emory University, born in Gulfport[84]

- Tim Young, professional baseball player, played for the Montreal Expos and the Boston Red Sox[85]

See also

[edit]- Dan M. Russell Jr. United States Courthouse

- Grass Lawn (Gulfport, Mississippi)

- Great Southern Golf Club

- Gulf and Ship Island Railroad

- Gulf Coast Military Academy

- Gulfport Army Air Field Hangar

- Gulfport Veterans Administration Medical Center Historic District

- Historic Grand Hotels on the Mississippi Gulf Coast

- List of mayors of Gulfport, Mississippi

- Mississippi Aquarium

- Mississippi City, Mississippi

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Harrison County, Mississippi

- Old Gulfport High School

- Turkey Creek Community Historic District

- United States Post Office and Customhouse (Gulfport, Mississippi)

- United States container ports

References

[edit]- ^ WXXV Staff (December 18, 2024). "City of Gulfport approves designs for new flag and seal, new motto". wxxv25.com. WXXV News. Retrieved December 18, 2024.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. August 12, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ "List of 2020 Census Urban Areas". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Early History". The Historical Society of Gulfport. Retrieved January 5, 2025.

- ^ "Handsboro". The Historical Society of Gulfport. Retrieved January 5, 2025.

- ^ Howell, Elmo (1992). Mississippi Scenes: Notes on Literature and History. Roscoe Langford. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-9622026-2-9.

- ^ Stephens Nuwer, Deanne. "Six Sisters of the Gulf Coast". Mississippi Encyclopedia. Center for Study of Southern Culture. Retrieved January 5, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Hellmann, Paul T. (February 14, 2006). Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-94858-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p National Register of Historic Places Registration Form | Gulfport Harbor Square Commercial Historic District (PDF). United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. 2012. pp. 27–30.

- ^ a b c d Cooper, Forrest Lamar (2011). Looking Back Mississippi: Towns and Places. University Press of Mississippi. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-61703-148-9. JSTOR j.ctt2tvknv.

- ^ United States Department of the Treasury (1904). Treasury Decisions Under the Customs, Internal Revenue, and Other Laws: Including the Decisions of the Board of General Appraisers and the Court of Customs Appeals. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 2ff.

- ^ National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form | U.S. Post Office and Customhouse. United States Department of Interior, National Park Service. February 7, 1984.

- ^ "History of Our Libraries". Harrison County Library System. Retrieved January 5, 2025.

- ^ Kennedy, Chatham (January 15, 2021). "Centennial Plaza". Mississippi Heritage Trust. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Gulfport Field". The Historical Society of Gulfport. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ a b National Register of Historic Places Registration Form | Gulfport Army Air Field Hangar (PDF). United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. 2012. p. 6.

- ^ "Air Force Base-Gulfport, 1954-1958". Mississippi State University Libraries. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ "Gulfport Civil Rights Wade-in". The Historical Society of Gulfport. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ "Hurricane Camille - August 17, 1969". National Weather Service. NOAA. Retrieved January 5, 2025.

- ^ Pielke, Jr., Roger A.; Simonpietri, Chantal; Oxelson, Jennifer (July 12, 1999). "Thirty Years After Hurricane Camille: Lessons Learned, Lessons Lost". sciencepolicy.colorado.edu. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ "Welcome to the Gulfport, MS Community". Armed Forces Retirement Home. Retrieved January 5, 2025.

- ^ Thames, Hardy (Winter 2013–14). "Looking for Justice at Turkey Creek: Out of the Classroom and into the Past". Civil Rights Teaching. Retrieved January 5, 2025.

- ^ "Anderson Cooper 360 Degrees: Hurricane Katrina Slams Gulf Coast". CNN Transcripts. August 29, 2005. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

that it felt like it would never end, saying winds were at least 100 miles per hour in Gulfport for seven hours, between about 7:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. For another five or six hours, on each side of that, they [Gulfport] had hurricane-force winds over 75 miles per hour; much of the city of 71,000 was then under water.

- ^ Fritz, Hermann M.; Blount, Chris; Sokoloski, Robert; Singleton, Justin; Fuggle, Andrew; McAdoo, Brian G.; Moore, Andrew; Grass, Chad; Tate, Banks (2008). "Hurricane Katrina Storm Surge Reconnaissance". Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering. 134 (5): 644–656. Bibcode:2008JGGE..134..644F. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2008)134:5(644). ISSN 1090-0241.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen L. (August 26, 2015). "On Mississippi's Gulf Coast, what was lost and gained from Katrina's fury". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ Tobias, Lori (November 18, 2019). "Nearly 15 Years After Katrina, an Aqarium Rises on the Gulf Coast". www.constructionequipmentguide.com. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ Perez, Mary (August 29, 2020). "Mississippi Aquarium brings generations for an opening day experience". The Sun Herald. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ a b "Geologic Unit: Gulfport". National Geologic Map Database. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "City of Gulfport Comprehensive Plan 2000" (PDF). Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Gulfport–Biloxi AP, MS". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ "Annual Comprehensive Financial Report 2020" (PDF). City of Gulfport, Mississippi. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ Ruppert, Tristan (August 29, 2020). "Mississippi Aquarium opens with VIP ribbon cutting, reception". Retrieved January 5, 2025.

- ^ "Mississippi Aquarium | Bids Opened for the Mississippi Aquarium Construction Contract". November 16, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2025.

- ^ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Turkey Creek Community Historic District)

- ^ Davis, Summer; Camp, Jason, eds. (2021). Municipal Government in Mississippi (PDF) (7th ed.). Starkville: Center for Government & Community Development Mississippi State University Extension Service. p. 33.

- ^ "Gulfport City Council". City of Gulfport. Retrieved July 19, 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Mayor". City of Gulfport. Retrieved July 19, 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ gulfport-ms.gov. "Gulfport-MS.gov | The Official Web Site for the City of Gulfport Mississippi". Gulfport-MS.gov | The Official Web Site for the City of Gulfport Mississippi. Archived from the original on February 12, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "MGCCC - Facilities - Jefferson Davis Campus". Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ "Tradition Campus | William Carey University". Wmcarey.edu. August 19, 2009. Archived from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "Gulf Park Campus | the University of Southern Mississippi Gulf Coast". Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ "About Us". The Sun Herald. September 22, 2015. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "Biloxi-Gulfport". Mississippi Press Association. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "'Our Tsunami's: The Sun Herald's Pulitzer Prize-Winning, post-Katrina Coverage". The Sun Herald. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ "FM Query Broadcast Station Search". FCC. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "AM Query Broadcast Station Search". FCC. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "WLOX History". WLOX. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "Stations for Biloxi, Mississippi". RabbitEars. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "WLOX-TV Wins Prestigious Peabody Award For Hurricane Katrina Coverage". WLOX.com. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "WATCH: Gulfport locations featured prominently in 'Precious Cargo' trailer". Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ "Gulf Coast is backdrop for Lifetime movie 'Christmas In Mississippi'". Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ "Gulfport businesses excited about premiere of Astronaut Wives Club". Retrieved October 8, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Alabama, Mississippi refuse to pledge money to resume Amtrak, create New Orleans route". The Advocate. Associated Press. June 22, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ "Trains". The Tallahassee Democrat. August 29, 2005. p. 2. Retrieved November 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Louisville and Nashville Railroad, Table 1". Official Guide of the Railways. 98 (2). National Railway Publication Company. July 1965.

- ^ Brey, Jared (August 8, 2024). "After 20 Years, Rail Service Returning to the Gulf Coast". Governing. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ Giardina, A.J. "The city of Gulfport honors Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf". WLOX13. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ Powell, Kevin (May 14, 2020). "The Power of Stacey Abrams". The Washington Post Magazine. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Ronald Reagan: Nomination of Thomas H. Anderson, Jr., To Be United States Ambassador to Barbados". Presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ Waldron, Travis (August 29, 2015). "From 'Katrina Kid' To Nebraska Quarterback: Tommy Armstrong Beats The Odds". The Huffington Post. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "Jerome Phillip Barkum". databaseFootball.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ "The Clinton Courier, William Joel Blass". Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ "Timmy Bowers". NBA Development League. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Rod Davis". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Brett Favre". databaseFootball.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Hardy (William H. and Sallie J.) Papers". The University of Southern Mississippi – McCain Library and Archives. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Josh Hayes". AMA Pro Racing. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Billy Hewes running unopposed for mayor of Gulfport". gulflive.com. Associated Press. March 18, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "University of Mississippi News: Attorney Boyce Holleman Remembered By Sons with $100,000 Gift to Law School". University of Mississippi News. May 14, 2010. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ Port of Gulfport (USA) / Mississippi State Port Authority (ID: 36200). Port of Gulfport (USA). p. 2. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ "Matt Lawton Stats". AMA Pro Racing. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ Billy Hathorn, "Challenging the Status Quo: Rubel Lex Phillips and the Mississippi Republican Party (1963-1967)", The Journal of Mississippi History XLVII, November 1985, No. 4, p. 240-264

- ^ "Brittney Reese". USA Track & Field. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "STUART ALLEN ROOSA (COLONEL, USAF, RET.)". NASA. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "#12 Tiffany Travis". University Athletic Assoc., Inc. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Natasha Trethewey". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Tim Young". The Baseball Cube. Retrieved November 27, 2013.